One thing without stain, unspotted from the world, in spite of doom, mine own!—And that is…my white plume!

-Cyrano, in Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac

In the Autumn of the year 1655, two hours after dawn, a sorcerer in a bottle-green coat drifted invisibly over the city of Paris, not far above the rooftops. His body upright, the magician sailed past chimneys, and, once, without pause, right through a steeple. He flew along about as fast as a raven flies, when it is in no terrible hurry, traveling wherever his mind chose to take him. When the magician came upon a certain district, he slowed, and descended toward a neglected, winding side-street. Here he stopped, just below the rooftops. The sorcerer hovered, and gazed up at three laborers, climbing a scaffold onto the roof opposite. One of them was a burly man in a long tattered coat, most of his face hidden by beard and matted hair. The burly man carried an oaken beam to the edge of the roof, where he could look down at the street. He stood there, holding the beam in his arms, waiting—just as the magician waited. The other two workmen glanced at the burly man, then looked quizzically at one another. But they were afraid to ask questions.

Well might they be afraid of him. The magician knew this man in the tattered coat to be a murderer. He had murdered in the past, and he had been sent here today to kill again, for a handful of gold.

Perhaps the murderer would succeed, the magician mused. Then again, perhaps not.

The sorcerer descended further, almost to the street. Unseen and nearly unseeable, he drifted just over the cobblestones, where he watched the front door of a tenement in which lived the poet, philosopher and soldier, Cyrano de Bergerac.

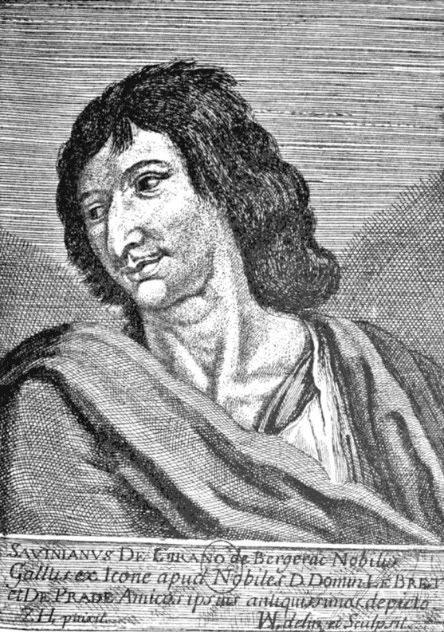

Cyrano Hercule-Savinien de Bergerac buckled on his sword, donned his ragged cavalier’s hat, with its large white plume—its panache—and hurried down the creaking wooden staircase.

He paused in the doorway to gaze out on the narrow street, assessing the late October day—a bit gray, but it was no longer raining, and with his prodigious nose Cyrano savored the multifarious scents of Paris: minerals released by the new rain, wood smoke combined with chamber pot’s reek, the smell of meat and pastry cooking; some blossom, somewhere—or was it a woman’s perfume? Gardenia?

Ragueneau was to meet him here, in front of the tenement—stout, genial old Ragueneau, the baker and poet. They would gossip over a quick breakfast, before Cyrano went to Roxanne. Most Saturdays, when he was in Paris, Cyrano recited his society news to Roxanne as she did her needlework. Some of his ironic “gazette” he would obtain from Ragueneau; some he would cheerfully fabricate. Anything to please his love—his unrequited love.

He had spent a good deal of time, recently, sequestered with Pierre Gassendi, steeped in the priest’s strange coalescence of Epicurianism, Christianity and atomism, and he yearned for the grounding of his old friends and for the forgetfulness he found in gazing upon Roxanne in the garden of the Ladies of the Cross.

He had been warned not to return to Paris, but he had been born here, and Roxanne was here, and he could not be away for long. And if a duel was offered him, so be it. It had been years since he had fought a duel, but—perhaps that was the very reason he needed one. In the world of philosophy one felt distanced from the visceral energies of life. Risk quickened the pulse; only Roxanne made his heart thunder more.

But in a duel, he reflected, as he stepped out onto the narrow lane of rain-wet cobblestones, a man might hope for consummation…

Somewhere close at hand voices were chattering away in gutter French—but not from the gutters, on the contrary, the gruff male voices nattered from the rooftops, as if the ghosts of Parisian scoundrels disported on the eaves. Workmen, he remembered, were to replace a decaying section of roof-beam today. So his sour-faced landlady had informed him.

There, to his left, came Ragueneau, walking through a small flock of strutting pigeons, the birds foraging at a heap of garbage; the pigeons took noisily to the air at the baker’s approach, fluttering near “the king of Bakers” like courtiers, Cyrano thought, applauding the approach of young Louis IV.

Ragueneau was still portly, Cyrano observed, though perhaps a bit haggard with some of the ill luck that had dogged the once-wealthy merchant in recent years. His eyes lit up at the sight of Cyrano. The pigeons fluttered and Ragueneau raised a hand—then those same eyes widened, his hand stiffened and he cried out in wordless warning—a shadow crossed Cyrano’s eyes and he felt the wind of the wings of death—

And suddenly both Ragueneau and the pigeons froze. The pigeons simply stopped in mid-air—yes and in mid wing-beat. The birds hung there, motionless, wings spread, like ornaments depending from a string on a windless day; Ragueneau was as motionless as the pigeons beside him, his hand upraised in warning, his mouth gaping, mustaches bristling as if to underscore the alarm in his eyes. Even more remarkably, Ragueneau’s right foot was raised in the air, had arrested fixedly there as if poised on an invisible stairway. But there was no stairway in the lane. There was just Ragueneau defying gravity—for, as he stood there with one foot lifted for a step that never completed, he should have been falling forward.

“Ragueneau?” Cyrano called, his voice sounding muffled and distant to his own ears, “What ails you? You seem to have gotten yourself stuck.” He began to move toward his old friend—and felt a sudden iciness sweep through him; a wrenching, as if he were torn from the fabric of the world.

For a moment Cyrano seemed to drift in the air a few paces, like a dandelion puff. He seemed unable to guide himself in the narrow lane; he turned randomly in the air, like whirling smoke—and, to his considerable shock, saw himself standing at his own front door.

He had left his body. So it seemed: he could see his own body, frozen in place, mouth open to call to Ragueneau; Cyrano frozen in place as Ragueneau was. There was a shadow on the frozen Cyrano’s face. It was cast by an object impossibly suspended, supportless, in the air over his head: a large piece of wood, roughly shaped into a short beam. This piece of beam looked to weigh about sixty pounds. But as it had fallen several stories from the roof—doubtless it originated with the workmen up there—its momentum would give it a great deal more force than a mere sixty pounds, Cyrano knew. When it struck him, it would stove in his head.

But it did not strike his body. It stayed motionless in the air, inches over his forehead.

And to see himself like this, so objectively…his mouth open, smiling, his head turned, one hand raising in greeting, the other on the pommel of his sword… He could see saliva glistening in his mouth; could see the oil on his skin, the pores on his nose. The rather large pores on his rather large nose.

Well, now. His nose, seen from this perspective, was not really as big as he had always supposed. The mirrors had perhaps exaggerated. It was rather big, yes. But really…

But that thought was washed away by the fear that swept through him, another internal gust: a keen wind from the highest, coldest mountain peaks. If his mind was torn from his body—surely he was dead!

Dreaming or dead, he thought.

“No,” came a sibilant voice “You are not dead. Not yet. You are merely outside the stream of time.”

“Who speaks?” Cyrano demanded. He was not himself certain how he spoke himself; with his mind or with some manner of ghostly mouth. “Show yourself!”

“I am behind your psychic perspective. Merely think of turning toward the source of my words and your spirit will respond,” said the voice.

Cyrano did so, and found his point of view rotating. He was now staring at the tenuous figure of a compact man in a bottle-green frock coat, a high collar, a leonine face; his hair was a mane of silvered black around his globular forehead; his eyes were small and piercing, seeming more substantial than the rest of his psychic form. The stranger floated a few inches over the cobblestones.

“What you see is a mere projection of my mind,” said the stranger. “My body is in a trance state in the south tower of my manse, which is in…ah, let us merely say that it is somewhere in Normandy. As for yourself, I have prodded your spirit out of your body—here in one of the crystallizations of a moment, in the necklace of eternity, a spirit is easily nudged free…although I must admit yours was a bit more tenacious than most. No doubt it was rather wrenching for you.”

“It was! And who are you, sir, to interfere with my spirit?” Cyrano demanded. “What impertinence! I insist that you meet me, fully bodied, and give satisfaction! You will choose your weapon, sir, and we will have it out!”

The stranger’s voice was all silky condescension. “Do you not see the wooden beam caught in its descent toward your head, you fool? Had I not interfered, you would now be dead! Expired! Pffft! And as for my identity, you may know me as Alcandre the Sorcerer; also known as Alcandre the Magnificent, Alcandre the Brilliant and Alcandre the Enviable.”

“Your reputation has not preceded you,” Cyrano said coldly. “And I do not believe in magic. Nor the soul—I was speaking facetiously a moment ago of my spirit. Nor do I believe in miracles—I have argued against them with devastating logic! Even Gassendi agrees with me, in secret. So I must conclude that I am dreaming—or I have taken opium, and forgotten that I have done so. Or possibly I have been poisoned, occasioning delirium. Each is more probably true than your magical freezing of time.”

“I have not said that I have frozen time. It continues. We are merely outside its stream—we are, as it were, perpendicular to it, so that we do not observe its passing, but are fixed, temporarily, and temporally, within the crystallization of a single moment. However, we haven’t 'time' for the full explanation: a variety of subsidiary time relating to the entropy of our spiritual selves holds sway upon you and me. And so we must proceed apace with our business. I have saved your life, sir, for the moment. But if I but reinsert you into your body and give you another nudge, your destiny will unfold as intended. The murder will proceed. And you will die. Or—you can do my bidding, and live!”

“Hold! What’s that you say? A murder? How so? Clearly it is an accident! Or—about to be.”

“No, monsieur. I regret to inform you I came upon the information that you were to be murdered, this morning. A team of workmen repair the roof, yes. But one of them is not a workman—he is unknown to the others. His employer has been bribed by a certain gentleman, who works, in turn, for a—ah, a member of the nobility. I do not know exactly which one. This mysterious nobleman has been desirous of ending your life for a long time. But then—you have many enemies. Many have been insulted by your writings, your declamations, and the, shall we say, insinuation of your sword, which always seems to suggest, without much repudiation, that the nobility is made up of cowards...since they have concluded to run from it. One such has arranged for that oaken beam to be dropped on your head as you emerge.”

“I insist you tell me his name! I will confront the coward!

I will—”

“I truly do not know his name,” the sorcerer interrupted, not very convincingly. “You have so many enemies! Who’s to say? I could find out, but it is not important to me. You will find out—after you have done a certain task for me. I will intercede, and prevent gravity’s own cudgel from falling on you. Then you will be free to make inquiries. You can then rush to the roof and interrogate the carpenters. But first…if you wish to live, and have your revenge, you will do as I ask.”

“And should I make an unsavory deal with an hallucinatory phantasm, sir?” Cyrano said, doing his best to sniff contemptuously. Difficult to do when one is pure spirit. “To have dealings with the excrescence of a dream? I would not so degrade myself. Again I assert the unreality of this event.”

“You are not dreaming; and I am no phantasm. I am unbodied, but I am quite real. Oh, you are right about magic: what people suppose to be magic is not magic. It is all science—all of it! But some is a science unknown to scientists! It will appear to be supernatural. As for the soul—some have one, while others have not developed one. The soul grows within a man like fruit in a tree. Most such trees grow in poor soil and are poorly tended, they produce no fruit. A few have a truly great, juicy ripe fruit—a truly developed soul! You sir—I became aware that you have just such a soul. A rare thing! A fairly solid soul that would not melt instantly away, once free of its body. The sort the Higher Beings rejoice in, when it ascends to their plane.”

Cyrano made a sound of derision. “Oh you knew I had this 'special soul', did you? Indeed? And just how did you know that?”

“Why—your plume sir. Your panache!”

“My panache? On my hat?”

“No, sir. The other sort. That is what you sometimes call it, no? It is—an expression of your essential being. A summarization that adds up to more than the factors of the equation. A gestalt of self expression which expresses far beyond your walk in life, although you are unaware it is doing so. It emanates, sir, because of your nature. It sends out a beam of spiritual light…or more accurately, a plume of light…that acts as a beacon, for those sensitive enough to perceive it. And with the guidance of this beacon, I found you. Thereupon, I saw this murderous event coming—which makes you particularly suitable, since, frankly, it gives me leverage for negotiation, yes?”

“This is all the false conjuration of a mountebank,” Cyrano protested, though feeling increasingly less convinced of his own convictions. “I don’t know how it’s done, but…”

“It is no false conjuration, monsieur. Look around. Do you not trust the evidence of your senses?”

Gazing again at his statuelike body, Cyrano had to admit to himself that he was in a place beyond his experience—and that it did not have the quality of a dream. It had the ineffable tang of genuineness.

Alcandre the Sorcerer nodded as if he’d read Cyrano’s thoughts. “Exactly so. Now heed me: Because of the power of your panache I can reintroduce your soul into your body. I will then introduce it into a—shall we say, a 'shortcut' in time and space, which will transport you to the time and the place where you will do the deed. There, a distance in the future—you will kill a tyrant! A tyrant who will be the scourge of the poor! A terrible tyrant the world is better off without! That is another reason I picked you: you are opposed to tyrants. Thus you are triply motivated: you have the chance to save your life, rid the world of a tyrant and seek out he who attempted to murder you. If only you perform this one task—kill the tyrant!”

“What tyrant is this?”

“Does it matter? When we pass beyond the edge of the worlds, and traverse time and space to his sanctuary, I will show you a bit of his wickedness. The wars I have foreseen—they will go on and on! The weighty taxation on the poor to build a gilded nursery for himself and his playmates! He is a monarchical absolutist…the very thing you despise! And he will trample France, the nation you love, under his perfectly formed, exquisitely booted feet!”

“And if you are so powerful, why can you not take this shortcut yourself, stab the fellow yourself, and take the same path to exeunt, eh?”

The sorcerer scowled. “I am not the only magician in this land. There is one, secretly engaged by Queen Anne, who still works for the crown—or more specifically, for that scabrous conspirator, Cardinal Mazarin!”

“Mazarin? The Premiere Ministre? Mazarin is a Jesuit! He would have no truck with a magician!”

“He would prefer it thus, true. But in fact that Italian wretch has become aware of my motions, certain conjurations of mine have come to his attention, and he has become alarmed. His own magician is a dwarf of sorcery, scarcely more than a mere chiromancer, but he stumbled upon a rather effective crystal of time-seeing and in it he saw that I intended to destroy the tyrant. He also saw that if I attempt the assassination in this year, it will fail; I have seen this as well. But in the future, matters are not so fixed! What is definite in the near-future is indefinite a little farther on. So we travel in time as well as space. Now, this malignant Jesuit set a swordsman to guard the tyrant against me: a lackey, a bootlick for tyrants. But—a great swordsman. I confess I fear him. You see—he, also, has…panache. His 'plume', too, is quite powerful, and I’m not sure I can manipulate him magically…and then again, there is the small matter of a charm, with a certain saintly relic inside; it has been placed about the tyrant’s neck by that low-rent alchemist. And that too keeps me at bay. But the charm will have no effect on you. And as for the swordsman—why, monsieur, you are well known to be the equal of any swordsman!”

“Ah well. In my day, perhaps.”

“You are only thirty-six! You are at your prime. Would you have your life ended at a mere thirty-six by a falling log? The ignominy! A great man like yourself? The author of The Death of Agrippine and The Pedant Imitated? The hero of the Siege of Arras and the greatest swordsman of Paris? But now, attend: Here is a fourth consideration to compel you: You will learn if you are indeed a more masterful wielder of cold steel than this…this oaf sent by the Cardinal to protect the tyrant. Unless…you are afraid?”

“I? I fear no man! I am Cyrano de Bergerac! I am…” His voice trailed off as he became aware of a dull rippling sensation in the vicinity of what had been his head. He was vaguely sensible that some aspect of this proposal was befogged by that rippling sensation. Some bell of warning rang within him: Beware. Something clouds your mind…

But he was overwhelmed by what had happened, disoriented by the loss of his body. And how he yearned to be reunited with it! This floating about was not something he understood. He was a man of action—not a wisp to be puffed away like the last exudation of a chimney! It was true, as well, that he did despise tyrants. And there was the matter of the murderer. And the chance to see Roxanne again. . .

“Yes,” Cyrano heard himself say. “I will undertake this mission—if you will return me to my body. Although how you can do it without permitting the unfortunate intrusion of this block of wood, I cannot guess. It would indeed be inappropriate for me to die thus, I who have shown that so many others were block-heads by comparison. And so, if you don’t mind, I dislike this vaporous state.”

His voice trailed off again as he found himself swirling like a human dust-devil. The figure of the Magus made certain sorcerous passes—and then Cyrano was falling through a spinning tunnel, back into…himself.

A wet reverberation, a metaphysical impact, and he was back in his body, standing, now to one side of his own doorway, staring at the short wooden beam yet hanging in the air over the spot where he had stood.

“But—time is still arrested!” Cyrano exclaimed.

“Yes. Your body now moves freely through the crystallization of this moment. It will also move a short distance into the future…and there it will rejoin the flow of time. Meanwhile, this moment will remain crystallized. You cannot move that beam from its place however hard you try! Later, you will return to this place, and this time. If you destroy the tyrant as I request, I will return you to this spot, but one step to the right of that falling block. Time’s flow will resume for you, and the block will strike the ground beside you. You will be unhurt and free to resume your life and hunt down your enemy. Free to see your Roxanne again! Free to live past a mere thirty-six years, to explore the outer reaches of philosophy! But if you do not do as I ask—you will be returned to the exact spot from which you were plucked. And you will be brained by that falling block! Do you understand the choice?”

“I do, Monsieur Magician.”

“Very well. Turn and approach the wall. Do you not see the crack there, in the wall? Observe! The crack widens! What was only big enough for an ant now gapes open sufficiently for two men to walk through, side by side! It is a transient opening through space and time…”

It was as Alcandre maintained: a crack in the wall of the building groaned and quivered and expanded, wider and wider. Within it was a churning quagmire of nascent possibilities…

Into which strode Cyrano de Bergerac.

No comments:

Post a Comment