by Adam Bolivar

The Moon’s my constant Mistresse

& the lowelie owle my morrowe;

The flaming Drake and the Nightcrowe make

Mee musick to my sorrow.

—Tom O’Bedlam

I.

Genealogy has always been a passion of mine. Little could I have imagined how close it would lead me to the very brink of madness. My grandmother had always maintained that we were descended from Sir Francis Drake, the legendary Elizabethan privateer. I have heard others make similar claims, that their families were related to royalty, or this or that famous person, but these assertions were never substantiated with factual proof, only rumor and family legend. Still, I imagine if one were to shake one’s family tree hard enough, a few notable apples would inevitably fall from the upper branches. Consider: every person has two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, and sixteen great-great-grandparents. Determined genealogists who comb the ever-propagating branches of their ancestries can doubtlessly connect themselves obliquely with almost any historical figures they fancy. It has been said that every person is at least the fiftieth cousin of every other human being on earth. But at this level, relation becomes dissolute to the point of absurdity. There must be a standard by which inheritance is determined, a means to establish lineage.

Obviously, a direct descendant would be favored over an indirect one. One is more apt to bequeath one’s fortune to one’s own child than to a nephew or a cousin. However, this standard can become impractical over time, for what if one begets more than a single child? The fortune must be divided amongst them, and then amongst all of their children, until at last the legacy is spread so thinly that it amounts to nothing. And what if there is a title, some singular honor that can only belong to one person at one time? Which of one’s children will inherit it? A rule, however arbitrary, must be adopted in order to determine who will be pronounced heir.

The two factors that present themselves as standards for inheritance are precedence of birth and sex. There are some traditions, such as the Iroquois and the Pictish, which reckon bloodlines matrilineally, and others that reckon them patrilineally. Each method is as arbitrary as a coin toss, yet each is equally useful. The English tradition is patrilineal—that is to say, one’s heir is one’s oldest and nearest male descendant.

Of course it thrilled me to no end to believe that I was a descendant of Sir Francis Drake, and I devoured any account of his life I could lay my hands on. I eagerly read of Drake’s exploits—his treasure-raids in the Caribbean, his heroic circumnavigation of the globe, and of course his triumphant clash with the Spanish Armada in 1588. The man had supernatural reserves of luck and cunning, and with astonishing ease he rose from his humble origins as a vicar’s son in Devon to become vice-admiral of the Royal Navy and one of the richest men in England.

The first proof of my relation to Sir Francis Drake came at my grandmother’s funeral, for death is always an event that shakes a family tree, and strange fruit can fall from its branches. I had always felt an ineffable connection with my grandmother, such as I felt for no other family member. We were of the same ilk, she and I—bookish, gentle and shy.

My mother telephoned to inform me of my grandmother’s closeness to death, and I immediately took the first train from Boston to Richmond to be at her side. The cancer was very far advanced, and my grandmother was in the throes of shedding her mortal coil. She could not speak, and passed in and out of semi-consciousness. I think she was aware of my presence and there was a haunted look to her earthy brown eyes. She did not want to go; leaving us behind would not be easy for her.

My mother, my great-aunt and I did our best to make her comfortable. It was on the morning of All Hallow’s Eve when she left. We were summoned to the hospital at the dawn of a clear, cloudless morning, though there was little warmth in the sun that day. I was not a witness to the moment of her passing, though I heard Azraël’s wings beating in the distance. I felt her still warm hand, but it was not a human hand. Her body was a husk now, and my grandmother no longer inhabited it. My great-aunt was cognizant of this fact, apparently, and without any ceremony, yanked the diamond wedding ring from her sister’s finger and gave it to my mother.

“I reckon this belongs to you now,” she said.

At the time I had thought this action to be somewhat callous, but my great-aunt explained it to me. “You have to take off the wedding ring right away after someone dies. If you don’t, the finger will swell up, and it becomes much more difficult.” She was over eighty years old, and had a considerable storehouse of experience with death to draw from. I filed this little piece of wisdom away in the vault of my memory for future use.

Now there was only the funeral to attend to, and a strange business it was indeed. Fortunately, my grandmother’s priest was able to guide us through the unpleasant necessities which accompany preparing and laying to rest a loved one’s earthly remains. My grandmother had chosen cremation as her means of returning to the elements. There was a subdued service in her beloved Episcopal Church, accompanied by the somber attire and lack of weeping which is the custom amongst Anglo-Saxons. No wailing and beating on the breast for us. Only the occasional tear out of the corner of the eye, which was quickly disposed of with a clean white handkerchief. Then the priest grabbed the box that contained the ashes of what was once my grandmother, and carried it out to the memorial garden where my grandfather had also been laid to rest, and my great-uncle as well. There was a hole already dug there, and the priest gently placed the box in the hole. He sprinkled a handful of earth on top of the box and recited the time-hallowed words, “Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust.”

She was gone. It was over. My grandmother was no more. I could not help but stare into the hole that had swallowed up my grandmother, wishing I could snatch her back into life again. But in the end, I had to turn away.

At this church it was the custom after a service for the congregants to assemble in a small annex nextdoor for tea, and this funeral was no exception to that rule. This gathering was more subdued than others I had been to, though it was interesting to see so many relatives assembled in one place. It was like a family tree brought to life. My great-aunt was speaking in hushed tones to a distant cousin of mine, whom I had heard tell of but never met, and neither did I meet him that day. At one point in their conversation though, he glanced at me with a knowing expression, and then turned to resume speaking to my great-aunt.

That night my mother and I slept in the empty house where my grandparents had lived, and finding that I could not fall to sleep, I stole out of my room to take a last survey of the house. My grandparents’ house was not a large one by any means. There was a master bedroom, in which my mother lay slumbering. There was a guest bedroom, in which moments ago I had lain restlessly beneath crisp white sheets. Now I was hunting, a lone wolf in the dark.

My instinct told me to go through the door to the attic, for any family secrets would be hidden in the attic. I was immediately greeted by a familiar musty smell, which brought back memories of childhood. The stairs creaked reassuringly beneath my feet. It was an organic feeling, as if the very wood beneath my feet were responding. I climbed the stairs and into my grandmother’s attic.

It was dark but for the light of the moon, which shone in through the bare, uncurtained window, and cast a silver glow into the darkened chamber. It would be an ideal location to perform necromantic rituals. Why should such an idea enter into my mind? It was only the beginning of such thoughts, as I would discover over the course of the next month.

The moon was shining in through the eastern window, and a shimmering finger of silver light (was it Lilith’s finger?) pointed at an old wooden wardrobe which sat in the middle of the attic and towered over the rocking horses and other forgotten relics of youth. The wardrobe. I was drawn ineffably to the wardrobe, as though some invisible force were pulling me forward. My hand reached out of its own accord and my fingers closed on the cold silver knob cast in the shape of an acorn. It was the acorn of a mighty oak, whose roots reached down deeply into the soft warm earth of time.

Inside the wardrobe were mementos of my grandparents’ life together: a white wedding gown wrapped in pink tissue paper and a suit of men’s formal wear. It was undoubtedly the attire my grandparents had worn on their wedding day. Sequestered out of sight in the back of the wardrobe was a cedar chest. I dragged the chest to the front, and opening it I found a stack of letters neatly tied together with a red ribbon. The letters were postmarked 1897... 1898... 1899...

Eagerly undoing the ribbon, I opened up one of the letters and strained my eyes to read the crabbed handwriting by moonlight.

Powhatan Sanatorium

December 21, 1899

My dear sister,

Would that I had never opened the cover of that accursed book! I shall always rue the day that I read those pages. Oh, I pray that you are never witness to the horrors I have seen. If you have an iota of sanity left, you will burn it until it is thoroughly reduced to ashes. If only I had the courage to do so myself. But I have learned the secrets that should never be known to Man, and now I am in their thrall. They will come for me soon, the strange winged things that flutter through my nightmares. Our only hope is with you now, sister. Burn the book! Leave no trace. Let our family’s terrible legacy die, as it should have centuries ago.

—J. D.

Beneath the letters at the bottom of the trunk was a large bundle of black wool, which had the pronounced musty smell of something that had been kept in an attic for a very long time. All my instincts told me to leave it undisturbed where I had found it, close the wardrobe, and go back to my bed. But alas, the Weird had not chosen such a tranquil path for me to follow. Perhaps it was the moon, the will of Lilith, or invisible puppet strings that impelled my helpless limbs. Slowly I unwound the swath of black wool, which had swaddled its contents for nearly a century.

It was a book—I knew that it would be—a large black book, like a Bible. The cover of the book was embossed with a coat of arms that I knew from my researches had belonged to Sir Francis Drake: two silver stars on a field of black, divided by a silver fess, waver. Queen Elizabeth had granted him these arms after his famed circumnavigation of the globe—the first Englishman to do so. Previously, Sir Francis Drake had attempted to use the traditional arms of the ancient Drakes of Ashe, but the head of that family, Sir Bertrand Drake, rebuffed Sir Francis’s claim for he could not prove his relation to them. He was, after all, of common birth, whatever his achievement in life.

But was Sir Francis Drake’s claim genuine after all? Was his family...our family...a branch of a far older line of Drake...the Dragon...whose roots stretched back to the days of the early Saxons...and further...to the very forest primeval where elves glowered and flashed their silver swords in a moonlit bower? Dare I open the book?

Of course I must. I had come this far. What kind of Drake would I be to shrink from this discovery and run cowering back to my bed? I opened the cover of the book and a folded document came fluttering down to the floor like an autumn leaf. Eagerly, greedily, I snatched up the paper and unfolded it. It was a pedigree, carefully drafted with an artistic flourish, which traced my family line from Sir Francis Drake’s brother Thomas to my great-great-grandfather, John Drake. With jubilant glee I revelled in the confirmation of my descent from Sir Francis Drake—an elusive fancy that I had nurtured from earliest childhood. But as I examined the chart more closely, I ascertained that there was another line, issuing from the oldest son of my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, James Drake. This line was of a higher precedence than my own, and threatened my claim to being the heir to the Drakes. This chart had been drawn a century before, and there was every possibility that this other line was now extinct. But how could I know for sure?

Crestfallen, I closed the book, and carefully wrapped it up again in the swath of black wool in which I had found it. At least the book was mine. I am not a Drake by name, but I am one by blood. The book had belonged to my great-great-grandfather, and I was its rightful owner. The moon had retreated beneath the clouds now, and it was in darkness that I had to stumble across the creaking attic floor. Carefully climbing down the narrow stairs, I clutched my inheritance to my breast and retreated to a cold sleep disturbed by fitful dreams.

The dispersal of my grandmother’s estate happened efficiently, for there are hidden, toothy mechanisms in place to dismember a person’s life as soon as it ends. For my part, I received a check for five thousand dollars, and another five thousand was allotted to the Episcopal Church. The house and whatever else remained of the estate were ceded to my mother. She has no siblings, and neither do I. The Salvation Army sent a truck to collect the closets full of clothes my grandparents had accumulated, and then our business was concluded. The shuttered house was locked for the last time until it could be sold, and I hastened to take the first train back to Boston, my strange inheritance stowed beneath the clothes in my suitcase.

Once back at my small apartment in Cambridge, I settled into my old routine and did not look at the book again, still bundled in musty black wool inside my unopened suitcase, which I had shoved to the back of a closet upon my return from Richmond. The peak of the colorful fall foliage had passed, and the streets became filled with piles of dead leaves as November wore on. I worked as a glassblower’s assistant then, and after trudging through miles of chilly wind wrapped in a coat and scarf, it was a relief to stoop before the hot furnace, heating bars of colored glass so that they drooped on the end of a puntil like melting honey, until the day came to an end, and I made my weary way back to my apartment in the darkness of premature night. It was not until many weeks later that I received the letter.

It was a night like any other early December night in New England—cold, star-speckled, and with a light sprinkling of snow on the ground. I came home from my job with sore limbs and an empty belly. The letter presented itself to me the moment I opened the mailbox. The pale blue envelope stood apart from the usual dreary concoction of bills and circular advertisements. Ignoring everything else, I snatched this prize from the box at once, and beheld it with wonder. My name and address were writ large on the front in black ink with a curving, archaic hand.

There was no return address, and the postmark was smudged, though I could make out the letters N.C., no doubt the state from which this missive originated. From whom could it be? I knew no one in North Carolina, though the place struck a chord with me, for I had run across this locality more than once in my genealogical research. I galloped up the stairs to my apartment, and bolting the door behind me, I zealously tore open the envelope.

My dear cousin,

First, let me express my heartfelt condolences at the death of your grandmother. I do not take the passing of any family member lightly. There are precious few of us left. I feel it is time for me to introduce myself. My name is Albritton Drake. We share an ancestor in common, and I think we may have other things in common as well. I would be honoured if you would consent to be a guest at my house. There is much we should discuss. Take the first train to Fiddle Creak, North Carolina tomorrow and I will have my driver meet you at the station. Bring the book.

Yrs most sincerely,

Albritton

I read and reread the short missive over and over, entranced by the sloping calligraphy, the texture of the cream-colored paper, the way the pitch black ink was absorbed by the fibers of the dry, thirsty parchment. It was a letter from a living, breathing Drake! My disappointment at learning that I was not Sir Francis’s heir was mitigated by this invitation to meet a bona fide Drake in the flesh.

But my mind was filled with questions. How did my cousin know where I lived? Why had I never heard about him before? And most mysterious, how did he know about the book which I had found in my grandmother’s attic? The book. It still lay in my unopened suitcase at the back of the closet. It was waiting for me, calling me. I knew that it was time for me to open it again, that I could dally no longer. There was an urgent quality to my cousin’s letter.

I drew back my curtains to look at the moon rising over the glittering skyline of Boston, plainly visible across the Charles River. It was nearly full, as it had been the night when I had found the book in my grandmother’s attic.

My cat Phaedra nuzzled my legs and meowed expectantly. Reflexively I stooped down to scratch her chin and stroke her long grey fur. I set the letter down on my writing desk and crossed over into the kitchen to fetch a box of cat food down from the pantry and pour a portion into Phaedra’s bowl. Yes, first things first, I thought. I did not know how long my visit would last, and I had to provide for Phaedra’s welfare while I was away. Leaving the cat to savor her long awaited supper, I took the spare key off of its peg and left my apartment. I strode down the hall to number 17.

Hesitating, I rapped three times in quick succession, followed by two more knocks—our secret code so that she would know it was I. I heard her familiar voice, made husky from smoking too many cigarettes.

“Just a minute.”

I waited, and a few moments later the door opened and there was Samantha, wearing her usual paint-spattered smock. Samantha was a graduate student at the Museum School, and over her shoulder I saw one of her pieces, an unfinished portrait of me seated on a wooden throne. A giant’s hand reached down into the perspective of the painting. The hand was poised to pick me up, throne and all, like a chess piece.

“Hi Hens,” she said, calling me by her own personal diminutive of my name. “You want to come in? I was just making tea.” There was an awkward pause—a familiar pause, redolent with frustrated passion.

“Sorry, I can’t,” I found myself saying, though some part of me yearned not to, the part that clung to life and love and hope. With a tremendous effort, I quashed that part of myself and shoved it back into the innermost recesses of my heart. “I have to pack for a trip. A cousin of mine has invited me to visit him at his house in North Carolina. I’m leaving tomorrow morning.”

It was an absurd thing to say. Why couldn’t I come in for tea? Would I need to pack all night? But I said it nonetheless. An ironic smile played across Samantha’s lips. She held out her palm to accept the key she knew I was about to place there.

“I suppose you want me to look after Phaedra while you’re gone?” she said.

“If you wouldn’t mind,” I answered, not meeting her gaze. I took the spare key out of my pocket and dropped it into her outstretched palm. Her hand closed around it.

“You know I love that kitty.”

“Thank you,” I said softly, almost in a whisper. “Well, I guess I’d better go.” There was a pause.

“Okay,” she said. I turned to head back to my apartment. There was another pause, and this one seemed to stretch on for an eternity, though it could only have been a few seconds. I thought Samantha was going to say something, and the part of me locked in my innermost heart desperately hoped that she would. But she did not.

“Have a good time,” was all that she said, and the door closed with a click. I shambled back to my apartment where Phaedra was waiting, curled up in a chair and purring contentedly now that her hunger was sated. It was time to open the book.

I bolted the door and turned off the lamps. Drawing back the curtains to allow the moonlight to stream into the room, I found a book of matches in my desk drawer and lit a half burned-down candle set in a dusty brass candlestick. I cannot say what drove me towards such ritual, only that once again I began to feel uncanny primordial urges, just as I had felt in my grandmother’s attic. Lilith had begun her dance.

Opening the closet door, I dragged out the suitcase. I undid the latches and opened the suitcase’s lid. The musty smell of a million attics engulfed the apartment and Phaedra rose from her slumber. The cat stretched her back and eyed my movements curiously. In the moonlight, her eyes shone an eerie emerald green.

The bundle of black wool lay at the bottom of the suitcase and I placed the bundle upon my writing desk. Phaedra arched her back and flattened her ears. Something about the bundle of wool tensed the cat, but she trusted me, and did not hiss or run away. Though not properly full, the moon exerted a considerable influence over the night. Lilith was dancing faster now. I unwound the black wool until the book was revealed, black and leathern, and I placed it lovingly upon my writing desk. The book. It was time.

Lifting the heavy binding of the book, I removed the genealogical chart that was tucked inside and unfolded it once again. I traced my finger down the lines of descent from Sir Francis’s brother Thomas—down the generations, across the Atlantic into the wilds of Virginia, and then North Carolina. Albritton Drake. He was the true heir. There were no dates associated with his name, but judging by his place on the chart in relation to the other names, he should have been a contemporary of those who lived and died in the eighteenth century. Surely not, I thought. The original Albritton Drake must have had heirs who were also named Albritton. It was a common enough practice in old families. There were certainly a number of Sir Francis Drakes, which was the name the English descendants favored. I would have to ask my cousin more about his particular line of the family when I met him.

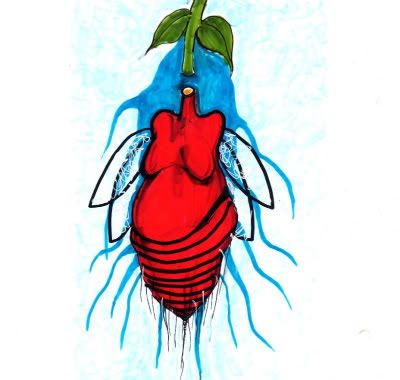

I carefully refolded the chart, obeying the creases that had been imprinted onto the paper generations before, and set it aside. Steeling the last remnants of my nerve, I peeled aside the flyleaf and beheld the frontispiece, which portrayed the profile of a wyvern—the ancient arms of the Drakes. The wyvern was depicted in loving detail, each individual talon on its feet sharply delineated, each scale on its knotted, barb-ended tail etched with miniscule perfection. No, the wyvern’s inky pupil did not just dilate. Its eye was not watching me with sardonic interest, threatening to swallow my very soul into its infinite abyss.

I forced my eyes away from the wyvern and moved them down the page to read the pompous black-letter printing, stamped by a press that long ago must have become worm-rotted timber in some Jacobean knacker’s yard.

Ye BOOKE OF MOONES

Printed by John Dee at the

behestt of Sir Frauncis Drake

London

1583

My mind reeled at the implications of this new knowledge. I had heard of John Dee, the magus and sometime court astrologer to Queen Elizabeth. Once revealed, the connection was obvious. Sir Francis Drake was a favorite of the Queen, and a prominent figure amongst the glittering array of personages that had made up her court. The two men had surely crossed paths. And if Drake had been interested in magic, whom else would he consult? I thought again of the legends that hinted at Sir Francis Drake’s dealings with the devil, and with a shudder quickly banished such notions from my mind. These were the gossipy tales of the ignorant peasantry of Devon, who also spoke of piskies and the headless hounds that haunted the trackless wastes of Dartmoor. I would give these dim murmurings no weight. And yet it was with hackles raised, with a freezing, unknowable fear that I turned the page and read on.

At that moment there was a gust of wind outside and the flimsy latch on my window gave way, causing the window to spring open and admit a frenetic burst of cold air, which billowed my curtains, extinguished my candle, and caused the pages of the book to flap madly like the wings of a bat. I hurried to fasten the window again, inserting a flat strip of wood beneath the latch to secure it, cursing myself for not thinking to do it before. I did not need to relight the candle, however, for the moon’s brilliant glow was more than adequate for me to read what was printed on the page. Did the wind open the book to this page by chance, or was something more than chance involved? Was this somehow a part of the dance of Lilith?

In the midst of a swirling sea of Latin, Greek and Hebrew letters, I alit upon a solid body of English, archaic in style, but easily understood. My lips began to move of their own accord. I read the words aloud—in a whisper at first, then louder and louder, until my ravings became as a wolf howling at the moon:

“Blacke Shepherde! Blacke Shepherde of the Wode! Hear me, thy humble servant, crawlynge vpon the duste to know but a tayste of thy Infinite Power. I ynvoke thee, Father of Darknesse, to fylle what cannot bee fylled, to reverse the Irreversible, to bringe Lyffe where once was Death. I have caste the sigills and scatter’d the powder’d bones. I have consecrated the Vessell of Kindred Blode. I svmmon the departed back across the yawninge Gulph beyonde the Gayte, where the Sentinell stands. I command hym who holds the Keye to openne the Gayte. In the Name of the Shepherde, openne the Gayte! Blacke Shepherde! Blacke Shepherde of the Wode!“

II.

I departed before dawn. The day broke brisk and bright over Cambridge as I dragged my battered old suitcase behind me and made my way to the Harvard Square T station through a flurry of snow. The events of the night before swirled around my head like some half-remembered dream, and yet I knew they were real. Blacke Shepherde! Blacke Shepherde of the Wode! The name was seared into my consciousness like a brand on the hide of a glassy-eyed cow. The invocation to which the pages of The Booke of Moones had inevitably opened, and which I was impelled against my will to read aloud, served some malevolent purpose. Yet that purpose was obscure to me. The only thing that shone through clearly in my memory was the sound of the scurrying of the rats in my walls after I had read the incantation aloud.

A man was smoking on the underground platform, but the station agent took no notice. The laws of the land were still drowsing at this early hour. Even the trolley car seemed sluggish, and I boarded it amidst a trickle of bleary-eyed commuters. The stations passed in a blur—Central Square, Kendall Square, Park Street, Downtown Crossing—until I reached my destination, South Station. I stumbled off the trolley with my burdensome suitcase before the doors snapped shut, and rode the squeaking escalator upwards, thankful for the small mercy that I did not have to walk up stairs. Now I found myself in the vast indoor arena of the train station. The usually bustling South Station was nearly deserted at the hour, and I approached the ticket counter without having to wait in the usual line of impatient travelers.

At first the clerk was thwarted as he tapped on his computer keyboard in search of my requested destination. Only after abandoning his accustomed technology and resorting to a little-used blue directory was he able to determine that there was such a place as Fiddle Creak, North Carolina, and issued me a ticket for a train due to depart in less than three minutes. I ran to the appropriate berth, and managed to scramble onto the train seconds before it pulled out of the station. Bells clanged and whistles blared. I flopped into an empty seat and watched as Boston flashed before my eyes and gave way to the sparser suburbs to the south. Fortunately, the uniformed train conductor arrived promptly to punch my ticket, so I could drift off into a deep slumber, troubled by dreams of a moor...

The moor appeared to stretch on endlessly, both in space and time, and at its heart was a circle of standing stones. Somehow I knew that I was in Britain, though I had never been there before. Was this an ancestral memory of Devon, or Cornwall perhaps? As I walked towards the stone circle, I passed by a herd of grazing sheep, as sheep had grazed here for thousands of years, and would doubtless graze here for thousands of years to come. One of the sheep was not like the others. It was a black sheep, a ram with a crumpled horn, and he gazed at me with ebon eyes, a gaze which pierced me to the soul. We were brethren, he and I; the black sheep and I recognized one another. But no, it was not a sheep. It was a barefooted shepherd, clutching a curling crosier, his face concealed beneath the cowl of a monk’s habit. It was the Black Shepherd. I passed by him hurriedly and stumbled toward the stones.

There were two men waiting for me. One I had seen before in portraits. He was garbed in a tight-fitting black velvet doublet, hose, and a ruffled collar as wide as a platter, in the style of Elizabethans. This could be none other than my famous ancestor, Sir Francis Drake. He gazed at me with avuncular kindness, and it seemed a hint of sadness, as one might feel for a sacrificial goat. The other was wearing the garments of the eighteenth century: brown frockcoat, tricorne hat and buckled shoes. Could this be Albritton? I do not know how I knew his identity, but then dreams have a logic all their own. Albritton held a formidable black tome under his arm. I recognized it to be The Booke of Moones. He exchanged glances with Sir Francis, who nodded, and said with a sonorous voice like rolling thunder...

“Fiddle Creeeeeak!”

I was jerked awake from my slumber. So soon? How long had I been sleeping? I peered out my window upon a lush landscape of well-ploughed pastures and green-leafed trees, so unlike the snowy cityscape whence I had come. I could almost imagine that it was spring again as I disembarked from the train, giddy with the scent of magnolia blossoms. I stood entranced at the sight of the Spanish moss swaying from the branches of ancient oak trees until my torpor was broken by the sound of a honking horn. A young moppet of a man with straw-colored hair hopped out of an impossibly new-looking Model T and hoisted my suitcase off the ground as if it were as light as a feather.

“Howdy do,” he said in a lazy Southern drawl. “Jack’s the name. Mr. Drake sent me to pick you up.”

I extended my hand, which Jack took into his and shook vigorously, as though he were working a water pump handle. Jack deposited my suitcase and its coveted contents into the trunk of the still idling Model T. Then he opened the passenger door for me like a chauffeur. Nodding my thanks, I placed my foot onto the running board and wearily hoisted myself into the leather-padded seat, which conformed itself comfortably to the contours of my body. Jack closed the door and hurried around to the driver’s side to take his place behind the wheel.

“Hold tight now,” he said, and winked at me as he put the automobile in gear. Despite its rumbling and groaning, the antique roadster navigated the bumpy dirt road with surprising smoothness. I inspected my driver with a curious eye. Jack wore a battered brown hat with a feather tucked jauntily into the ribbon. Faded blue overalls covered a threadbare flannel shirt from which most of the buttons were missing. The only thing new about Jack’s outfit was a pair of shiny black oxfords, one of which was busily operating the Model T’s clutch. Jack caught me admiring his footwear out of the corner of his eye and laughed. I averted my gaze guiltily.

“Nice shoes for a country boy, huh? Mr. Drake gave ’em to me in boot for some odd jobs I do for him. I reckon they came out of his own closet. Fit me like a glove though. Now don’t that beat all?”

I could only dumbly nod my agreement, too fatigued to muster the energy to make small talk. Instead I looked out the window and admired the scenery. To the right of the road a sprawling estate became visible, lorded over by a stately white mansion faced with a columned portico. For a moment I thought that this must be our destination, but Jack did not slacken the car’s speed, and the house flashed by and began to recede into the distance behind us.

“That’s ol’ Boss Straw’s plantation,” Jack volunteered, sensing the question in my mind like a cat scents a fish in the kitchen. “He’s a mean ol’ timer to work for an’ his purse is tighter than an old maid’s apron strings. My cousin got a job of work from him once an’ Boss Straw said that he’d cut three strops out of my cousin’s back if he ever got mad. Well my cousin got mad all right, on account of Boss Straw made him work for three days without giving him a bite to eat! An’ then he cut three strops out of my poor cousin’s back just like he said he would.

“Well, I fixed Boss Straw’s wagon good. I hired on for a job of work myself an’ he made the same conditions. So I asked him if I could cut three strops out of his back if he ever got mad. Boss Straw said I could, so I fooled around, ate all the food out of his pantry, cut down all his apple trees an’ kissed his wife for good measure. Well, Boss Straw got madder than a swarm of bees after you knock their nest down. So I wrastled him to the ground an’ served him just like he served my cousin. Cut three strops out of his back. One two three. Hee hee!”

I chuckled politely at Jack’s story, which had the ring of a fairy tale, though he told it without a hint of irony. There was something fairy tale-like about this countryside into which I was entering deeper and deeper, leaving behind sanity and the world I knew. The words from the book echoed in my head, as I drifted off into haunted slumbers once again. Blacke Shepherde! Blacke Shepherde of the Wode! I was awoken from my nap by Jack’s cheerful drawl.

“Here we are. Buckland Manor.”

I opened my eyes and found that we were parked in front of a formidable looking manse of red brick walls and steep white gables, a relic of the vanished glories of the Southern planters. Judging from the grandeur of this estate, the scions of my cousin’s branch of the family were obviously folk of wealth and prominence. They were aware of their descent from Sir Francis Drake, for the house had been named after the Admiral’s own estate in Devon, Buckland Abbey. I wondered why these Drakes were not mentioned in the official histories of Sir Francis Drake’s family. Jack came around to open the door for me, and I stepped out onto the gravel, which crunched beneath my feet.

There was a man standing in the doorway of the house. This could be none other than my cousin, Albritton Drake. He regarded me with a strange smile, and gave a little formal wave, which I returned awkwardly. My cousin was wearing a tailored tweed suit, and though his attire was not as antediluvian as it had been in my dream, he was unmistakably the man I had seen standing in the circle of stones. Jack hauled my suitcase out of the trunk of the Model T.

“I’ll jus’ take this on up to the guest room for ye,” he said. “Then I’d best get on home. Ma’ll be expecting me to do a couple of chores ’fore suppertime.” Before I could thank him, the genial young man with the faded overalls and shiny new oxford shoes carried my suitcase across the lawn and, tipping his hat to my cousin, disappeared into the front door of the house. It was time for me to meet my host.

As I drew nearer, I noticed that there was something strange about my cousin’s attire after all. The cut of his suit jacket was higher than usual, and he wore a stiff, detachable collar of the kind popular at the turn of the century. To complete the image of a gentleman from another time, a gold watch chain ran across his vest. Albritton Drake extended his right hand, a gesture I returned and our hands clasped in a firm embrace.

“Welcome, cousin,” he said, in a grave, masculine voice appropriate to his age, which I judged to be about fifty. “You must be tired after your long journey. Why don’t you go up to your room and refresh yourself? Dinner will be served in an hour and we can talk then. I’ve no doubt you have many questions you want to ask me.”

“Thanks,” I managed to reply. “That sounds great.”

My words were not eloquent, but they were all my overtaxed brain could come up with. Entering the front door I was overwhelmed by the opulence of my cousin’s house. A crystal chandelier hung from the ceiling, and as I climbed the marble stepped staircase, I passed by a row of portraits of noblemen dressed in the garments of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These must be members of the Drake family, I ascertained, and they peered out from the oil with piercing, haughty eyes as a dull and disheveled offshoot of their line shuffled past their vanished splendor. I was the poor relation.

The door to my room was open. I shut it and, fully clothed, flopped wearily on top of the neatly made bed. I longed to have a proper night’s sleep before meeting with my cousin, but I could only drowse for half an hour before necessity forced me to rise and attend to the trivialities of my toilet, which were performed with the aid of a pitcher of water and a washbasin. Evidently, the luxuries of modern plumbing had not yet arrived in this part of the country. I donned the same black suit I had worn to my grandmother’s funeral and descended the staircase to dine with my cousin. The suit was somewhat wrinkled now from lying in a suitcase for a month, but it was my best.

Albritton met me in the foyer and escorted me to the dining room, which was already set with a variety of regional delicacies—roast pork, sweet potatoes, black-eyed peas and collard greens. My cousin seemed intent on putting on a show of Southern hospitality. He was obviously proud of the land his branch of the family had adopted as its home. We were attended to by a sad, rat-faced footman wearing formal attire, though my cousin was still sporting the same tweed suit he had worn earlier, probably in deference to my own lack of evening wear. His graciousness was impeccable. Once we were seated and glasses of Burgundy wine were in hand, my cousin started to make conversation.

“Let me offer you my sincerest condolences on the passing of your grandmother,” he said. “The loss of any member of our family is of course a great tragedy to me. I regret I was not able to attend her funeral, though I was given news of it by our cousin Bampfield.”

Bampfield, I thought. He must be the man at my grandmother’s funeral that my great-aunt had been conversing with.

“His family is only related to the Drakes by marriage, of course. However, our houses have been allied for many generations.”

“I’m very interested in the history of our family,” I said. “But there are some gaps in my research. I was hoping you might be able to fill them in. From what I understand you are the closest successor to Sir Francis Drake himself.”

Albritton arched an eyebrow, perhaps surprised that I had come to the point so quickly.

“Indeed,” he replied. “Sir Francis Drake’s nephew, also named Francis Drake, inherited the estate, for the Admiral had no children himself. In recognition of the wealth and prestige which come of being the heir to such a famous man, King James I created Sir Francis’s nephew the Baronet of Buckland Monachorum, an hereditary title. He was the first baronet, and he had a line of successors until the fifth baronet died in 1794. It was assumed in England that the fifth baronet was the last of the line, and the title was considered extinct. However, there was another line that was not accounted for. The youngest son of the first baronet had a grandson who emigrated from England to America before the Revolution. He was our mutual ancestor. When the last English baronet died, the title rightly passed to me, for I am the oldest of the direct male line. I am the sixth Baronet of Buckland Monachorum.”

I paused in mid-chew of a mouthful of greens, and was forced to wash it down with a swallow of Burgundy. I noticed that my host had not touched his own food.

“The sixth baronet? You mean your ancestor was the sixth baronet, don’t you? I thought you said the fifth baronet died in 1794.”

My cousin fixed me with his disconcertingly pale blue eyes, and I shivered. There was something very old in those eyes, something cruel and not of this world.

“There are many things which you should know, cousin—first of which is that you are not in fact my cousin. You are my nephew. My great-great-great-great-great-nephew.”

My fork clattered to my plate. I at once lost all appetite for eating, delectable as the meal was. As if sensing this fact, the black and white garbed footman removed my plate. I seized the glass of Burgundy and took a healthy gulp.

“But that would make you...”

“Two hundred and thirty-five years old, yes. I am not accustomed to being so forthcoming with such information, but the circumstances force me to accelerate my disclosure. The Blood Moon is tonight. I trust you have brought The Booke of Moones?”

Dumbly, I nodded an affirmation. My cousin’s—no, not my cousin—my great-great-great-great-great-uncle’s manner became brisk and businesslike.

“It is well. I think we are finished with the formalities of dinner. Would you be so kind as to fetch it for me? I will meet you in the library and we will continue our discussion there.”

III.

The library of Buckland Manor was every bit as impressive as I would have imagined. I felt like an initiate to some society of Gnostic mysteries as I crept into the sepulchral chamber, the echoes of my footsteps disturbing the silence of the hushed cloister. Stacks of books ascended to the vaulted ceiling. Some of the books so old and arcane they looked as if they would crumble to fairy dust at the slightest touch. Albritton was waiting for me there, looking impatient and feral as his eyes fixed greedily on the bundle of black wool, which I clasped to my chest. My relative appeared older than he had before, gaunter and paler. It was as if his human appearance were only a glamour, an illusion that was rapidly fading as its usefulness became outlived.

“The book,” he rasped, in a much higher pitched voice than the one he had been using earlier. “Is that the book?”

“Yes,” I answered nervously, becoming more aware now that surrendering the book to his possession may not be the wisest of courses. “I have it.”

“My younger brother Benjamin—my half-brother to be precise—uncovered our family’s secret work, what we have been plotting for so many generations, and unable to accomplish. He stole The Booke of Moones from out of the library and claimed to have burned it. I would have killed him with my own hands, brother or no, but Father loved him better than me and would not punish him. Father was a fool! For the last two centuries I have kept myself alive by sorcery, feeding on the life’s blood of animals, and the occasional infant when need be, and traveled the world in search of certain grimoires, trying to retrieve the knowledge that was lost to us. I found fragments, tantalizing scraps in Old Solomon’s Book and The Secret of Secrets, but the key was missing—the invocation of the Black Shepherd. Then I discovered that my dear brother had lied! He had not burned the book at all—he had only hidden it. The book had been passed down through the generations of his descendants, and now it has come to you, dear nephew. But the book does not belong to your branch of the family, which does not even bear the ancient name. It is mine. You will return it to me. Now.”

Against my will, my feet propelled me towards my mad uncle. Though I resisted with every atom of effort I could summon, Albritton’s wizardry was too powerful. He snatched the bundle from my grasp and cackled with delight. The last vestige of humanity had deserted him now, and I beheld Albritton Drake for what he was—a gibbering, two-hundred-year-old ghoul.

“Now Benjamin,” he crowed in a high-pitched whine, a voice which was more demon than human. “Your descendant will pay the price for your trespass against our family’s work. The Admiral will walk the earth again in this new vessel of flesh which I have procured for him, for only one of our own blood is worthy enough for his spirit to inhabit. The Drakes will be mighty, as we were in the old times. Silvae Pastor Atratus!”

There was a click and one of the bookshelves swung open to reveal a secret passageway behind it. Whatever mechanism operated the assembly had apparently been triggered by the Latin phrase he had just spoken. My body was still not under my own control, and I followed helplessly in Albritton’s wake into the unutterable darkness, which swallowed me like a hungry maw.

We descended a flight of stairs that led to a mazy catacomb beneath the house. A musk of death lingered in the catacomb, a whiff of slavery and cruel secrets, of a family tree gnawed at the roots by its evildoings as Nidhogg gnaws at the roots of Yggdrassil. The darkness was nearly total, but Albritton traversed the catacomb with the eyes of a ghoul and the surety of twenty decades of familiarity. I followed a few feet behind him, my every movement aping his, for my body was in his thrall.

After what seemed an eternity, the catacomb came to an end. We had walked what I estimated to be a half a mile when we came to a flight of steps carved from living rock, ascending to an aperture into the night air. I found myself in a clearing in the forest, surrounded on all sides by poplar trees. At the sky’s zenith, where there should have been a full moon was only a dull red orb. The Blood Moon. The only light came from the stars, which shone as pinpricks in the cold December sky. After so long in the darkness of the catacomb, my eyesight was acute, and I was astounded to see a circle of standing stones arranged in the center of the clearing—the same stones I had seen in my dream. I saw Albritton as well, and his appearance was more ghoulish now than ever. His eyes were sunken into their sockets and his flesh was stretched tightly over his bones. My relative resembled nothing more than an animated corpse. And yet he was full of energy, hopping from foot to foot like an imp.

“I removed these stones from Cornwall, and smuggled them to North Carolina for the ritual. According to the Admiral’s letters, Dr. Dee had insisted that these stones must be used and no others.”

I wanted to cry out for him to stop, but I could not even command my own vocal cords. Not that Albritton would have paid any heed. He was far too absorbed in his work. Unwinding the black wool from around the book, he placed the terrible heirloom atop the flat stone in the center of the circle. The altar. Albritton—if it truly were Albritton Drake, not merely the vehicle for some alien entity—slowly, reverently began to open the book’s cover. At that moment, a voice rang out in the darkness.

“Howdy do!”

Albritton’s concentration was abruptly shattered by this unexpected exclamation and his spell over me was broken. I was able to wrest free from his mental clutches at last, and turned my head to see a straw-haired moppet of a man wearing overalls and a battered felt hat standing on the edge of the clearing. It was Jack. He waved at us and flapped his elbows like a chicken’s wings.

“Cock-a-doodle-do!”

Albritton Drake emitted a shrill piercing shriek, and then ran towards Jack with what could only have been the intention of rending him limb from limb with his bare hands. But the maddened ghoul never reached his grinning tormentor. The ground collapsed beneath Albritton’s feet and he fell into a deep pit, which had been concealed by sticks and grass. It took me a moment to realize that Jack must have dug the pit earlier as a trap. And that was not the only preparation Jack had made. Hefting a formidable looking pickaxe, which until then had been hidden in the scrub, Jack nimbly leapt across to the lip of the pit before the spry ghoul could scramble out.

“Tantivy!” cried Jack as he brought the tip of the pickaxe crashing down onto the ghoul’s head. Albritton Drake was no more. The Booke of Moones lay open on the altar stone, its pages flapping wildly in the breeze, as if the book itself were angry at having its intentions thwarted. With all my strength, I forced the cover of the book shut and rewrapped it in the swath of black wool. Jack clapped me on the back.

“I reckon you’re Mr. Drake now,” he said. I paused a moment to consider. Of course he was right. Now that Albritton was dead at last, I was the heir to the Drakes. I knelt down at the edge of the hole and examined the twisted remains of the ghoul who had been my great-great-great-great-great-uncle. The facade of flesh was withering like old leaves and in a matter of seconds, there was nothing left but a skeleton wearing a tweed suit. On the finger of the skeleton’s hand was a gold ring. I slipped the ring off the skeleton’s finger and held it in my palm. It was a signet ring, engraved with the coat of arms of the Drakes. My birthright. Was this the talisman that had given Albritton the power to manipulate my actions? Given him life when there should only have been death? I dropped the ring into the hole with Albritton’s bones.

“We should bury him,” I said. “And then we should set fire to the book. I think it’s for the best.”

“I reckon so, Mr. Drake,” Jack smiled. “I reckon so.”

The next morning Jack drove me back to the train station in the Model T, which I had given to him for his services. Buckland Manor was mine now, and I would have to think long and hard as to what I should do with my haunted legacy. As we drove away, I cast my eyes back at the sprawling manse, with its centuries of secrets tucked away beneath the steeply sloping gables. I had not been able to find a trace of the rat-faced servant who had served me dinner the night before. I wondered if he had been but a phantom, or a ghoul like his master. I must admit I had not tried very hard to look for him.

The book proved impossible to burn until we unwrapped the black wool in which it was swaddled, and then flickering red flames shot up from the leather binding like the very fires of Hell itself. I thought I could hear Sir Francis Drake’s shade roaring with rage as the pages crackled, a wolf howling across the gulf beyond the Gate, and then all was silent. Only ashes remained. Jack asked me if he could keep the wool. He thought it would make a fine shawl for his mother. I gave it to him as a trophy. After all, he had killed the tiger. It was only right that he should have its skin. Jack waved to me from his shiny new roadster as I boarded the train.

“Come on back now, y'hear? You’re welcome in Fiddle Creak anytime. I’ll have Ma whip you up a mess of hominy and grits an’ I’ll drive you anywhere you want to go!”

I may return to Fiddle Creak one day. One day. But for then I settled back in my seat as the train pulled out of the station and rocked me gently to sleep. No more did I dream of stone circles and ancient gods. This time I dreamt of Samantha.